Ugento in Messapian, Roman and medieval times

Back Ugento in Messapian, Roman and medieval times

Ugento in Messapian, Roman and medieval times

Although sporadic finds allow us to hypothesise at least the presence of the site since the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods, there is some evidence of a first settlement on the top of the Ugento hill, corresponding to its southern part, which is now the historical centre, from the Late Bronze Age (12th-10th century BC)

Ugento in Messapian, Roman and medieval times

Although sporadic finds allow us to hypothesise at least the presence of the site since the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods, there is some evidence of a first settlement on the top of the Ugento hill, corresponding to its southern part, which is now the historical centre, from the Late Bronze Age (12th-10th century BC); in fact, the remains of a small village of huts from this period have been excavated in the Castle area and a little further south, in Piazza S. Vincenzo (fig. 1). Subsequently, an Iron Age village of huts seems to be in direct continuity with that of the Late Bronze Age, as attested by the findings of “impasto” of the 9th-8th centuries BC in the Castle area and of pottery of the 10th-9th centuries BC from Piazza S. Vincenzo, while in the nearby Vico Milelli the remains of a hut have been found together with pottery with geometric decoration of the late 8th-7th centuries BC.

The archaic-age settlement developed in direct continuity with the Iron Age village and is characterised by masonry buildings that overlap with the huts of the previous phases. In this phase the settlement extends in the central-southern sector of the hill, where, in the area called Colonne, there must have been one or more important sacred areas, such as the one where the famous bronze statue of Zeus was found, created by Tarantine artist in the final decades of the 6th century BC and originally placed on a column erected in a sacred enclosure. The most important necropolis associated to the city was located on the immediate eastern slopes of the hill, in the Borgo area along the Via Salentina, where the monumental "Tomb of the Athlete" was found, built at the end of the 6th century BC and used until the beginning of the 4th century BC. The archaeological documentation of the archaic period highlights the precocity of the contacts between Ugento, on the one hand, and Taranto and Greece, on the other, with the acquisition by the local elites of ideological conceptions and typically Hellenic customs, carried out thanks to the close relations they had to maintain with the Magna Graecia and Greek aristocratic classes, in particular the Corcyraeans.

Already in the archaic period, Ugento must have been one of the most important city-states in Messapia, governed by basileis with civil, religious and military functions. As far as the classical period is concerned, it should be stressed that the strong presence of artefacts imported from Taranto, especially in the latest phase (late 5th-early 4th century BC) of the "Tomb of the Athlete" is the direct consequence of the cultural penetration of Taranto in southern Messapia, which continued throughout the 4th century BC. This was also accompanied, again in the second half of the 5th century BC by an intensification of relations with Athens, which in this phase was interested in Messapia for its strategic position from an anti-Tarantine and anti-Syracusan perspective and which is reflected in the Attic imported materials found in the same "Tomb of the Athlete", or in other funerary contexts, such as that of via Aghelberto del Balzo.

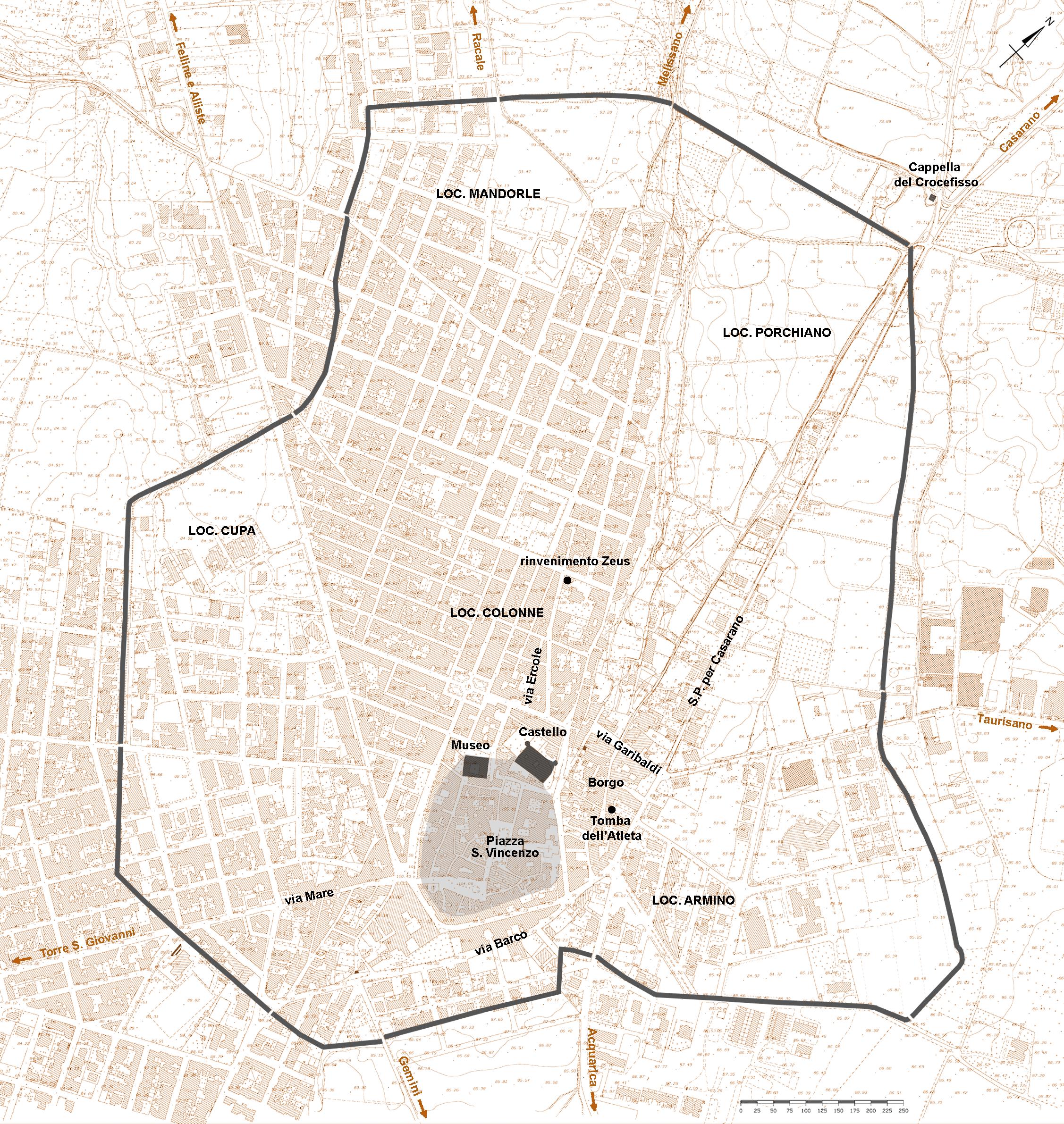

The period between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC seems to represent the phase of maximum development of the Messapian settlement, which takes on a clearly defined structure and is delimited by an imposing city wall, probably built in the middle or second half of the 4th century BC enclosing an area of almost 145 hectares, which makes Ugento the largest centre in Messapia (figs. 2-3). The area enclosed by the walls, which included a large part of the hill and large flat strips on its slopes, consisted not only of settlement areas, but also of necropolises; these were generally found on the edges of the residential areas and in the peripheral areas of the area enclosed by the fortifications, often along road axes leading out of the town, both immediately inside and outside the walls. The main nucleus of the Messapian settlement still occupies the area of the historic centre and that area immediately to the north (Colonne), where public buildings, both civil and religious, were probably also located, such as those to which the buildings must have belonged. Architectural elements of the 4th-3rd centuries BC, some of them bearing Messapian inscriptions, have been found here several times since the last decades of the 19th century; also the remains of a rather regular road system have been identified, which could date back to the Hellenistic age and which will also continue to be used in the imperial era. Also on the hill, another settlement nucleus of the 4th-3rd centuries BC, with areas associated necropolises, must have occupied, according to the available archaeological documentation, its north-western part (the locality of Mandorle), crossed by a road axis running northwards from the area of the historic centre. In the flat areas on its slopes, however, other settlements can be seen in the Armino area (between the modern streets of D'Azeglio, Fermi, Marconi and Volta), along a road axis which, that went down from the hill to the east , at the base of the south-eastern slope between via Urso and via Barco, along a road running approximately north-east/south-west, now partly taken up by via Barco, and on the western slopes, always along an ancient road axis, between the present via Mare and via Monsignor De Razza. Two blocks of Doric frieze and architrave have also been found here, one of which bears a Messapian inscription dating from the second half of the 3rd to the end of the 2nd century BC, perhaps containing a public document and belonging to a civil or religious building. A final inhabited area extended to the locality of Porchiano, in the northernmost part of the area enclosed by the walls, near a route that left Ugento in a northerly direction and which is now traced by Via Madonna della Luce.

From the beginning of the 3rd century BC, Ugento, like the other centres of Messapia, was confronted with Roman expansionism, first alongside Taranto and then, after the fall of the latter (272 BC), in the Roman-Sallentine war, which ended with the victories of the Roman consuls of 267 and 266 BC. In the following decades, despite the loss of its political independence, the city maintained a relative internal autonomy thanks to a foedus aequum with Rome, which obliged it to provide the latter with contingents of infantry and knights in case of need. I In this phase Ugento still maintained typical Messapian cultural characteristics and in the last decades of the 3rd century BC, also issues a bronze coin with the legend AO, probably an abbreviation of AOZEN, in which the Messapian name of the centre can be recognised, adapted to the Greek toponym Οὔξεντον, later attested by Ptolemy (Geogr., III, 1, 67). In this regard, it should be remembered that the ethnic Αὐζαντῖνος/Ἀζαντῖνος is attested in two Greek inscriptions of the 3rd-2nd century BC found in Delos.

The conflict with Rome was aggravated by the Hannibalic war, when, as Livy recalls, (XXII, 61, 11-12), after the battle of Cannae (216 BC), the Uzentini broke their alliance with the Romans, and sided with rhe Carthaginians. However, the Roman reconquest of Manduria and Taranto as early as 209 BC, also meant the end of the autonomy of Ugento, which must have been attacked and conquered by the Romans shortly afterwards. As recent archaeological excavations in the Cupa area have shown, the Romans forced the city to demolish its walls, which were gradually dismantled from the 2nd century BC, and turned into a large stone quarry, which continued to be exploited throughout the Middle Age and the modern times. Moreover after the Roman conquest, the city may have suffered the imposition of a tribute and the confiscation of part of its territory.

Overall, the 2nd century BC in Ugento is characterised by the presence of both elements of continuity with the previous period and caesuras. The former includes the persistence of the use of the Messapian language and the issue of a series of coins, following the Roman weight system, but maintaining the Messapian legend OZAN; an important change instead concerns the funerary ritual, since from this moment cremation, foreign to the Messapian ritual and introduced by the Romans, gradually became established.

The Romanisation process then seems to have become more significant after the Social War (90-88 BC), when Uzentum may have been conferred the status of municipium; this hypothesis would been confirmed by a fragmentary inscription from the late 1st century BC or early 1st century AD which perhaps mentions a quinq(uennalis), therefore a municipal magistrate in office for five years. Between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC the settlement seems to have maintained much of the structure of the previous phase (with the main nucleus occupying the central-southern sector of the hill and other secondary nuclei in the surrounding areas), although some peripheral areas are already tending to be deconstructed, according to a phenomenon that became more evident during the imperial period. Moreover, the necropolises were now more clearly located in the peripheral areas. In general, Ugento while maintaining a certain importance and a central role in the control of the surrounding territory, seems to have been affected by a process of gradual decline in the late Republican period, also as a consequence of the progressive "marginalisation" of the Salento peninsula from the wider circulation dynamics of the Roman world. This is also evident from the funerary objects, which lack imported materials and in which, unlike the previous phases, no particularly relevant and high-level contexts can be discerned, indicating a still strong and dynamic aristocratic class.

The archaeological presences of the imperial period document a progressive reduction in the areas occupied by the settlement and a probable ruralisation of some sectors of the territory included in the circuit of the Messapian walls, in particular those located on the western slopes of the greenhouse. The literary sources do not provide any particular information about Ugento, while among the itinerary sources it is significant that the Tabula Peutingeriana (VI, 5-VII, 2) reports Uzintum together with some other centres located south of Lecce-Lupiae, namely Otranto, Castro, Nardò, Alezio and Vereto, proving that the centre still had a certain importance in the territorial structure of the lower Salento. In particular, Ugento appears along the road between Taranto and Capo di Leuca, the so-called via Sallentina, between Balesium and Veretum, both X miles away.

As in the previous phases, the main nucleus of the town includes the area of the historical centre and the area immediately to the north, but it is possible that the settlement contracted southward between the middle and late imperial ages. Two other residential areas, in close continuity with the previous phase, are then found on the north-eastern slopes of the hill, in the Porchiano area, and further south, in the Armino area, where in this phase there is a complex built with large parallelepiped blocks of calcarenite, partly also covered with painted plaster; associate with it is a large cistern also made of blocks and covered with cocciopesto (fig. 4), built in the late republican/early imperial period and used until the middle imperial age, and at least one mosaic floor. Some funerary areas have been identified on the outskirts of these two cores; among them, a small necropolis from late antiquity stands out, with pit and sarcophagus burials, found in the Crocefisso area, near an area where a large medieval cemetery will be found.

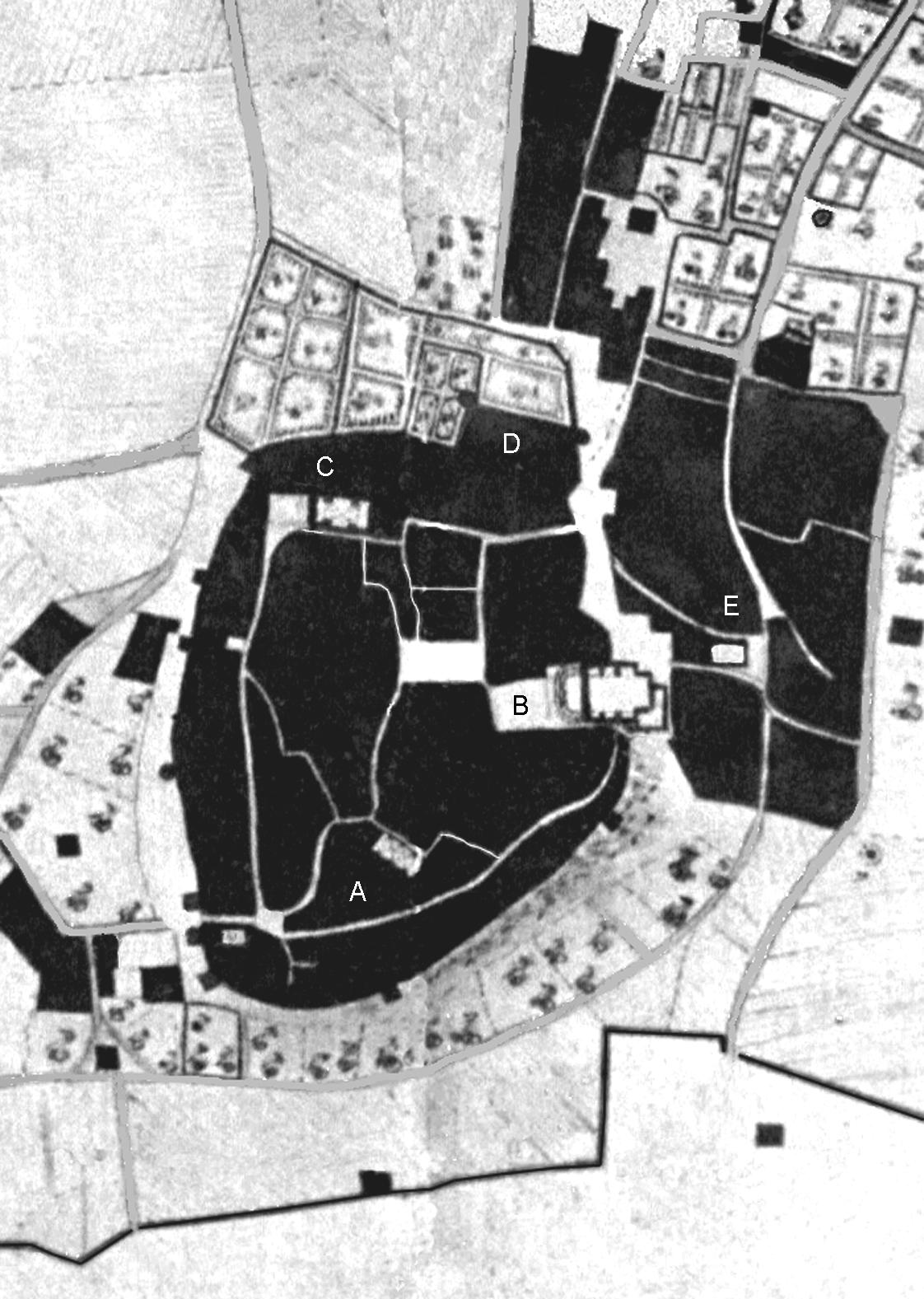

In the early Middle Ages, the settlement was concentrated at the southern end of the hill, in the area now occupied by the historical centre, in an area of just over 4 hectares (fig. 5). In the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire, southern Salento passed first under the Ostrogoths and then under then Byzantines and was only slightly affected by the events of the Greek-Gothic war. Later, around 876, Ugento was destroyed by the Saracens of Sawdān, the emir of Bari. A building revival then took place with the Normans, who were also responsible for the construction of the first nucleus of the castle, at the northern end of the town in the 11th century (fig. 6); this was then extended in the following centuries, especially by the Angevins, and gradually assuming its current appearance, which is the result of renovations carried out between the mid-16th and 17th centuries; between the second half of the 17th century and the 18th century, the Marquises D’Amore, who became the owners of the castle, transformed it into a noble residence eliminating most of the defensive structures. In the Middle Ages the building had a precise strategic location, on a hill that allowed it to control a large part of the territory and at the same time to protect the town on the side that was least naturally equipped; in fact, the walls that delimited the settlement to the east, south and west, , about 800 metres long and equipped with two gates (one open to the north-east and the other to the south-west, towards the sea, called " Porta del Paradiso” and “Porta di S. Nicola”) ran along the edge of the plateau at the top of the hill, which here rises 10-15 m above the ground on its immediate slopes.

At the end of the 12th century there is the first mention of the Diocese of Ugento, but it is uncertain whether it is of more ancient origin and dating to the centuries before the destruction of 876. On the eastern side of the hill, under the direct protection of the castle, an external village developed along the via Salentina, just to the north of which, between that is now via Garibaldi and the S.P. Ugento-Casarano, there was a 13th-14th century manufacturing district with pottery kilns. To the north of the historical centre, along Via Ercole, there was a necropolis with burials in earthen pits, probably near a road that led north from "Porta del Paradiso". On the south-eastern slopes of the greenhouse, along Via Barco, other medieval wall structures have been identified, where the remains of a large building used between the 12th and 13th centuries and in the 14th century have been brought to light, including warehouses and an artisan workshop with kilns. Finally, about 1 km north of the town, in the locality of Crocefisso, there is the Crypt of the same name, a small underground church dating back to at least the 13th century, around which there was a large medieval necropolis; connected to a rock settlement a little further north, the rock building exploited an outcrop of calcarenite rescued from a quarry already in use in the Messapian period and located along one of the main routes leading north from Ugento.