L’Antiquarium

Back L’Antiquarium

L’Antiquarium

Along the corridors of the first floor of the Museum, there are various displays related to the first exhibition containing ceramic, clay, metal, and stone materials, mostly decontextualised.

The Antiquarium

Along the corridors of the first floor of the Museum, there are various displays related to the first exhibition containing ceramic, clay, metal, and stone materials, mostly decontextualised.

Ceramic materials [corridors A, B, and C, displays 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

In various displays along the corridors of the first floor, numerous ceramics are displayed, grouped by vascular shapes. These are mainly materials of local production, sometimes regional and, in very rare cases imported from Greece, mostly dating between the 6th and 3rd centuries BC. The material is intact and well preserved, although there is no information about the context in which it was found, it is almost all funerary.

The largest vases are the kraters, from the earlier with columnar handles to the most recent bell-shaped with banded decoration, phytomorphic with long branches of leaves or geometric (fig. 1); less attested are the black painted examples with decoration overpainted in white, red and yellow. The krater, used to mix wine with water, is present in male tombs together with oinochoai or jugs, used for serving, and skyphoi and cups for drinking; these shapes are made with black paint, also overpainted or with banded decoration.

There are numerous examples of trozzelle, the typical vase of the Messapian civilisation, used to contain and transport water and closely associated to the feminine sphere and domestic activities. The examples in the Antiquarium, both large and miniature, are decorated with vegetal motifs sometimes alternating with geometric motifs (fig. 2).

Closely linked to the funerary ritual are the commonly used forms in such as plates, lekanai, cups, and cups which were intended to contain food offerings and were therefore placed in the tombs regardless of the sex or age of the deceased.

The small vases containing ointments and perfumed oils can be attributed to body care: the black-painted lekythoi, but also made in the red-figure technique, were replaced in the Hellenistic period by the black-painted, banded, and achromatic ointment jars.

The black-painted feeding bottles, some small vases and the miniaturistic vases, achromatic or brown-painted, with handles on top can be attributed to the burials of infants.

There are also numerous examples of lamps in the Antiquarium, well attested in funerary objects, with clear traces of use, such as the blackening of the spout. Most of the lamps are black or unpainted and can be dated to the Hellenistic period, although there is no shortage of Roman examples with beaded motifs on the shoulder.

The terracottas and clay materials [corridors A and B, displays 4 and 11; room 2]

In the displays of the Antiquarium there is a small number of figured terracottas. These are fragmentary statuettes, both male and female, made from tired matrices and with difficult-to-read attributes.

In the collection of figured terracottas, a unicum consists of a pinax, a clay slab depicting a female figure inside a chapel, the pediment of which has a central roundel and two lateral columns (fig. 3). The figure is standing next to a column on which her left hand is resting, while her right hand, rises the hem of her dress. A small hero in the upper right, crowns the female figure, perhaps Aphrodite or a bride. These objects are very common in the sanctuaries of Magna Graecia between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC, where they were hung as votive offerings in sacred precincts or inside temples through small holes at the top.

Among the terracottas, some tintinnabula stand out, animal-shaped rattles with a clay ball inside that act as a clapper. Our specimens, which can exceptionally be attributed to a specific context of discovery, were found in a tomb discovered in via Madonna della Luce; they represent an infant, with his head missing, crouching on a pig (fig. 4). The type is attested in Messapia between the 4th and 3rd centuries. BC both in sanctuary contexts, such as at Oria-Monte Papalucio, and in children's grave goods. Of particular interest is the clay reproduction of a bunch of grapes made by adding clay globes to a core. These objects were placed in sanctuaries or tombs to replace perishable offerings.

Also noteworthy is the matrix of a clay disc with phytomorphic motifs arranged on two concentric bands: the outermost one with lotus buds and flowers and the other with palmettes alternating with lotus flowers. In the central disk, there is a Gorgon's head surrounded by snakes.

There are also many loom weights and spindles associated with weaving. Most of them have the shape of a truncated pyramid with impressed decorative motifs, sometimes simple fibulae or letters.

The bronze materials [corridor A, display case 2]

One of the display cases of the Antiquarium contains various bronze jewellery and instruments. There are numerous examples of fibulae, frequently attested in funerary contexts for their function as clasps on both men’s and women’s clothing. In most cases they are simple arch fibulae, with a bracket ending in a conical element, which in some cases also retain the spring and needle; the specimens can be dated to the Archaic and Hellenistic periods. Of particular interest is a pincer fibula, so called because of the characteristic shape of one of the ends that replaces the spring, well attested in northern Italy in Roman times; in the example from Ugento the characters IIXII, of uncertain meaning, are engraved on the arch (fig. 5).

Several bronze fragments refer to belts made of a metal sheet band, closed with hooks fixed on it with variously decorated plaques: from the simple palmette to the stylized human or animal figures (fig. 6 and 7, n. 2). An integral part of the armament worn by warriors, the belt is attested in male tombs as a valuable object and constitutes a clear indication of the individual's wealth.

A clear indication of the productive activities that took place in the Messapian centre of Ugento is the bronze fishing hooks, easily recognisable by the hooked end of the rod (fig. 7, n. 3). The specimens preserved in the Antiquarium are comparable to those found in Torre San Giovanni, the port of the ancient Messapian centre.

The steelyard used for weighing small loads is also related to trade and exchange activities. The graduated rod with a square section is preserved from the specimen, ending in a knob, on which the weight values are engraved (fig. 7, n. 1). The two rings placed at one end of the rod and fused to it were used for hanging weights.

The sculptural materials [corridor A, display case 3]

Like other cities of Messapia, Ugento also must have had statuary decorations, especially in its sacred areas and necropolises. Very few elements of these statues remain, having survived the destruction and reuse as building materials.

Two of the artefacts exhibited in the Museum can perhaps be traced back to the funerary monuments of Messapian Ozan. The first is a female statue made of compact limestone (max. height 49 cm), of uncertain origin, depicting a young woman with a long dress (chiton), held by crossed straps on her chest (fig. 8): the thin and tight folds, the arms detached from the body and the barely three-quarter view seem to suggest that the figure in movement. The particular shape of the dress, with crossed straps, recalls the Caryatids of Vaste, statues that introduced the entrance to a monumental tomb from 300 BC: this comparison suggests that the figure from Ugento could also have belonged to the furnishings of a prestigious tomb dating to the 4th or 3rd century BC. The dynamic pose and the reproduction of the drapery suggest that the author of the statue could have been a sculptor trained in the Taranto area.

Hypothetically, a small youth head (max. height 18 cm) made in “pietra leccese”, with large wide-open eyes, thick eyelids and deeply inserted under the eyebrow arches was found in 1970 along via Salentina, in the Borgo on the eastern slopes of the old town of Ugento and can be assigned to a funerary monument. The head is characterised by long, swollen and curly locks of hair that frame the face, topped by a tubular diadem (fig. 9). Although the state of preservation does not allow for a precise evaluation; it could be assumed that it is the full figure of a young man, originally placed in a small temple tomb (naiskos). All the distinctive elements of the head are found in the funerary sculpture of Taranto, such as the tubular diadem, attribute of young deceased people, gods and heroes, and the hair swollen in curls, attested in the representations of warriors and heroes of Taranto, while the emphasis on the gaze is linked to the formulas of the late-classical production of the sculptor Skopas of Paros (ca. 375-330 BC). Finally, the hair and the diadem could be echoes of the iconographies of the Hellenistic kings found in Taranto in the monumental tomb of via Umbria (first half of the 3rd century BC). Also in this case, therefore, it is possible to think of workers linked to the workshops that were active in Taranto between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

These sculptures, together with a youth's head from the Colossus Collection and a small sema base with battle scenes from the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto, also from Ugento, demonstrate the local reception of ideological models and funerary customs typical of the wealthy classes of the Greek colony of Taranto.

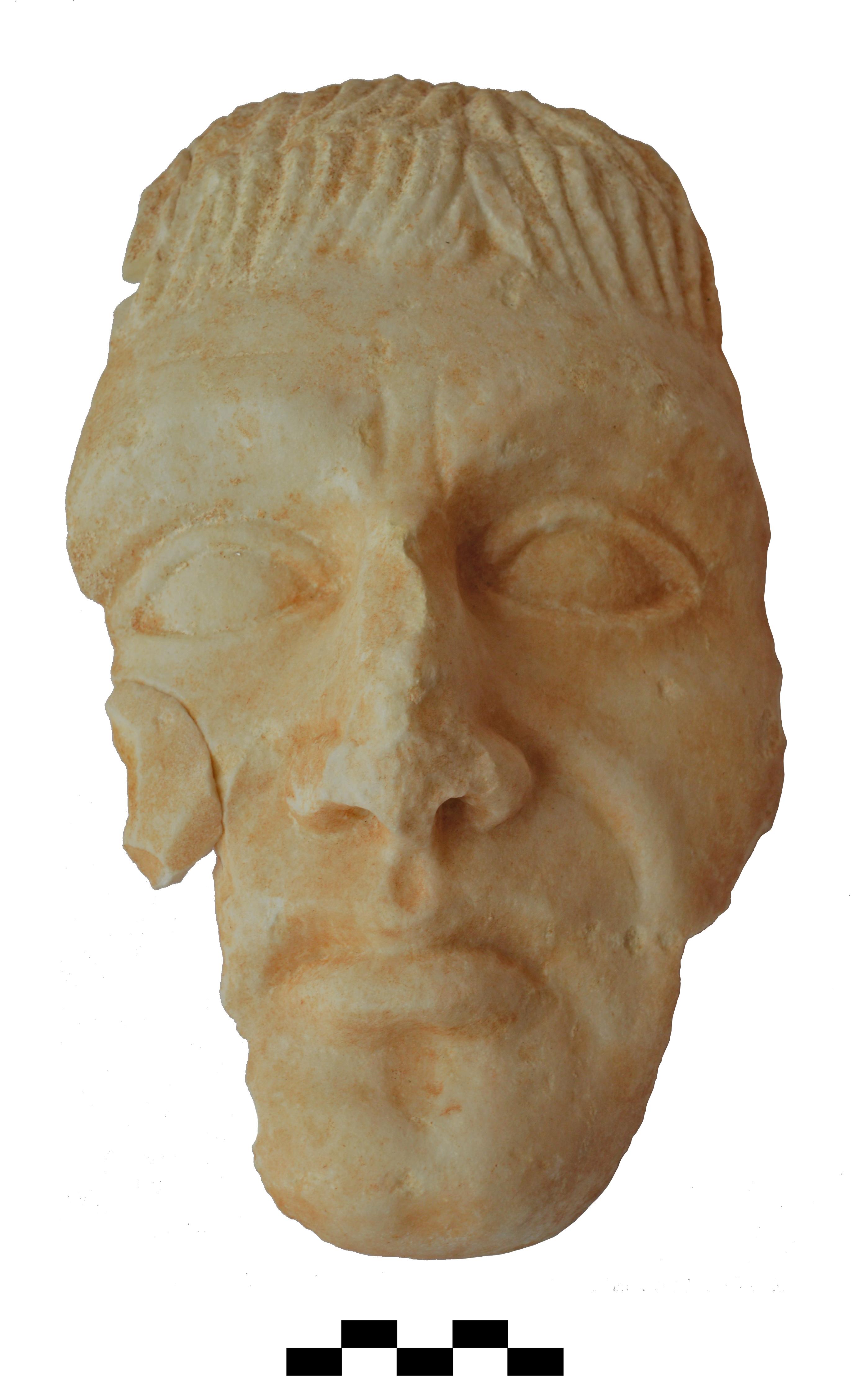

A long period of time separates these works from a male face in white marble, a minimal part of which has been preserved, found in 1968 inside an unspecified tomb in the Santa Croce area, in the flat area south-west of the hill on which the old town of Ugento stands. . Despite its small size (max. height 26.5 cm), this head can be attributed to a portrait statue of the late Republican age: the hair in locks under the two registers forms a high fringe (fig. 10). The wisdom, firmness, and self-control of mature age are indicated by the wrinkles on the forehead, at the root of the nose, and on the sides of the tight mouth with full lips, as well as by the fixation of the large eyes, defined in a non-naturalistic way by the raised eyelids that protrude incongruously to the outer corner. Hair, mature age, and severity lead Ugento's head back to Roman portraiture of the 1st century BC, with comparisons between the 70s and the middle of the century. The statue, perhaps full-figure or bust, can be imagined both in a public space of the city and in a funerary context: it can perhaps be attributed to one of the notables of the late republican Uzentum, who seems to adhere to the conventions and values of the Roman elites.